An Unseen Light by Unknown

Author:Unknown

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University Press of Kentucky

Published: 2018-04-15T00:00:00+00:00

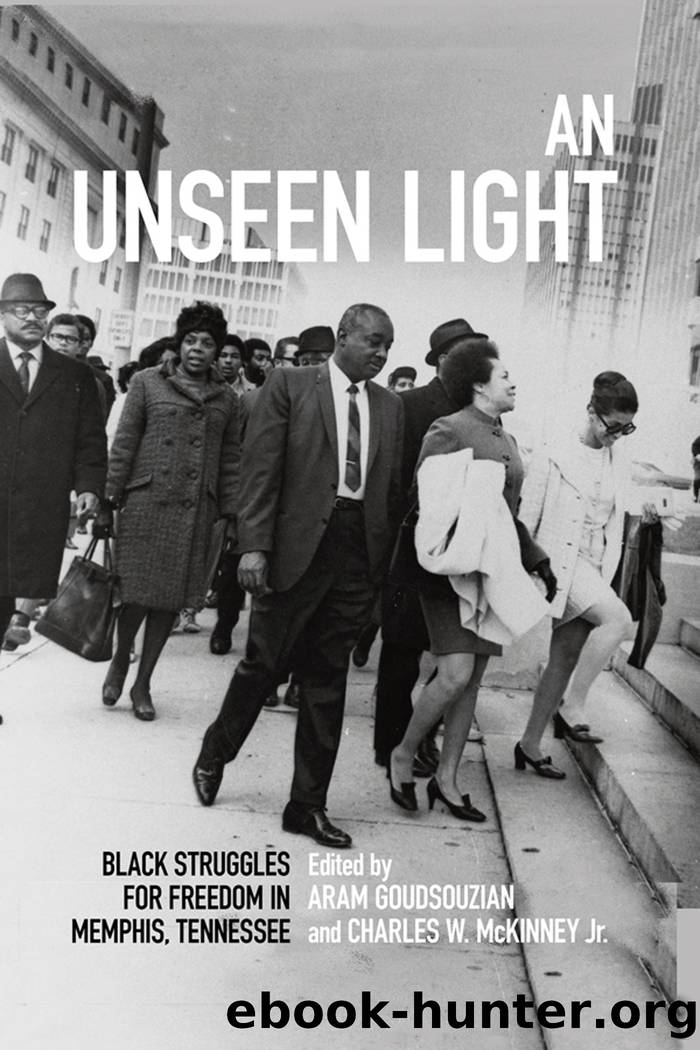

LeMoyne College students arrested after Cossitt Library sit-in, March 19, 1960. (Courtesy Special Collections Department, University of Memphis)

The âgutsy, wonderful kids ⦠threatening the status quo by fighting peacefully for first class citizenshipâ galvanized the Memphis civil rights community.49 Maxine Smith recalled that the executive board of the local NAACP branch was meeting to discuss plans for a Memphis sit-in movement when it received the call to come bail out the library protesters.50 Lawyers Russell Sugarmon and A. W. Willis were quickly dispatched to the jail to arrange for the protestersâ release.51 The proceedings lasted several hours. Judge Beverly Bouche set the bond at $352 for each protester, totaling $14,432 for the group.

In the meantime, a hastily arranged mass meeting on Saturday evening at the Mount Olive Christian Methodist Episcopal Church drew ministers from numerous churches, and they promised to call on their congregants to contribute money for the sit-in movement.52 The meeting also resulted in the adoption of a statement for the press, which read: âThe Memphis Branch of the NAACP ⦠wishes to declare its wholehearted support of these students, their objectives and their non-violent demonstrations. This branch further pledges its moral, financial and legal resources to assist them in achieving these goals.â53 By the time the bond hearings began at 10:30 p.m., the NAACP had rounded up $5,270 in cash and put up corporate bonds for the remainder.54 The police entered the church at around 1:15 a.m., nightsticks in hand, to clear out the building, threatening to âlock you up for loitering on the streets at 1:30 a.m.â55

The library protesters, released in groups of fifteen or so, were greeted outside the jailhouse by a jubilant crowd of about a hundred people and escorted to a gathering in a residence at 519 Vance Avenueâright next door to the Negro branch of the library.56 As they were released, most of the protesters declined to comment for the press, although Ed Young served notice that âWe have just begun to fight.â57 When asked why she was at the library, Gwendolyn Townsend told a reporter, âI felt that since I was a citizen, I had the right to attend the library.â58

The arrests were not inconsequential. The Tri-State Defender ceased publication for a week until its staff could file their reports.59 A number of students were fired from their part-time jobs or domestic work.60 Despite the approbation they received in the press, not all the studentsâ families were pleased. Marion Barry recalled that his motherâs first reaction to the sit-ins in Nashville had been to reprimand him: âBoy, what are you doing in jail?â61 The long-term fate of most of the Memphis protesters has not been tracked, but Fred Jones, one of the Greensboro sit-in pioneers, was blackballed from employment after his graduation.62

The Sunday following the first sit-ins, African American churches were filled with sermons urging support for the protesters. Herbert Brewster noted that the students âwere merely applying Gandhi and Nehruâs tactic of passive resistance to compel the white race to

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The 5 Love Languages: The Secret to Love That Lasts by Gary Chapman(9815)

The Space Between by Michelle L. Teichman(6941)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(6223)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5787)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4743)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(4654)

Pillow Thoughts by Courtney Peppernell(4284)

A Simplified Life by Emily Ley(4163)

The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale(4065)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3360)

Resisting Happiness by Matthew Kelly(3341)

Girl, Wash Your Face by Rachel Hollis(3282)

Being Aware of Being Aware by Rupert Spira(3276)

The Secret Power of Speaking God's Word by Joyce Meyer(3220)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3189)

More Language of Letting Go: 366 New Daily Meditations by Melody Beattie(3030)

Real Sex by Lauren F. Winner(3023)

Name Book, The: Over 10,000 Names--Their Meanings, Origins, and Spiritual Significance by Astoria Dorothy(2987)

The Holy Spirit by Billy Graham(2953)